ABC-Z (or ABC to Z) began as a project from 2015-2017 to update the Albuquerque-Bernalillo County (ABC) Comprehensive Plan, a joint effort by the City and the County and, within the city only, to overhaul zoning (Z) and other land-use/transportation provisions into an Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO) that regulates how development looks and feels.

That's A (Albuquerque), BC (Bernalillo County) all the way to Z (Zoning).

See a video describing the Comp Plan update here.

See a video describing the Zoning update here.

Purpose

The ABC-Z project began in 2015 as a 2-year effort to update the Comprehensive Plan and consolidate many overlapping and conflicting regulations into a new, user-friendly Integrated Development Ordinance. The ABC-Z project continued on as the City's commitment to continually improve policies and regulations based on input from an ongoing, proactive community planning on a 5-year cycle.

This coordinated system of planning seeks to:

- Implement the updated ABC Comprehensive Plan.

- Update existing adopted land development policies and regulations, particularly those related to coordinating land use with transportation systems and encouraging mixed-use development.

- Encourage development that creates high-quality, vibrant destinations connected by corridors that offer multiple options for getting around safely, whether by driving, walking, biking, or taking a bus or other public transit.

- Ensure protections for established neighborhoods and special places.

- Ensure equitable and effective planning in every community in the city.

These three parts of the ABC-Z project — the Comp Plan, IDO, and CPA Assessments — work together to achieve community vision and support the growth of a more equitable, sustainable, and prosperous Albuquerque.

The City is only one actor in the commitment to good community planning. Communities already have many strengths to build on. Community organizations, institutions, and individuals all have a role to play. In addition to fostering and promoting connections among many actors and factors of change, the assessment process will generate recommendations for changes to policies, regulations, and projects that the City can implement.

Project History

In April 2014, the City Council adopted Resolution 14-46 (Enactment No. R-2014-022), which directed the Planning Department to update the Rank 1 policy document (the Comprehensive Plan), overhaul the City's land use and zoning framework, and update the City's technical and engineering standards related to development in the Development Process Manual.

In January 2015, then-Mayor Berry announced the start of ABC to Z - an ambitious three-year project to update the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Comprehensive Plan and to integrate and simplify the city’s zoning regulations and technical/engineering standards to implement the resulting plan.

Project Success

The project updated the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Comprehensive Plan to:

- Reflect growth trends and challenges

- Better integrate land use and transportation planning – to reduce traffic congestion and encourage transit-oriented development

- Emphasize “Placemaking” approaches to development in key centers and corridors

It also created a new Integrated Development Ordinance that:

- Is simpler, more user-friendly, and highly illustrated

- Is better aligned with Albuquerque planning priorities

- Protects established neighborhoods

- Promotes sustainable patterns of development

- Updates and removes inconsistencies in outdated engineering and technical standards

- Streamlines the city’s procedures for reviewing and approving new development

Finally, this project updated the Development Process Manual to incorporate standards for City streets to:

- Be more flexible in order to better support transit and other public infrastructure investments.

- Incorporate Complete Streets standards to work better for pedestrians and bicycles as well as automobiles.

- Manage stormwater in more sustainable ways.

Project Team

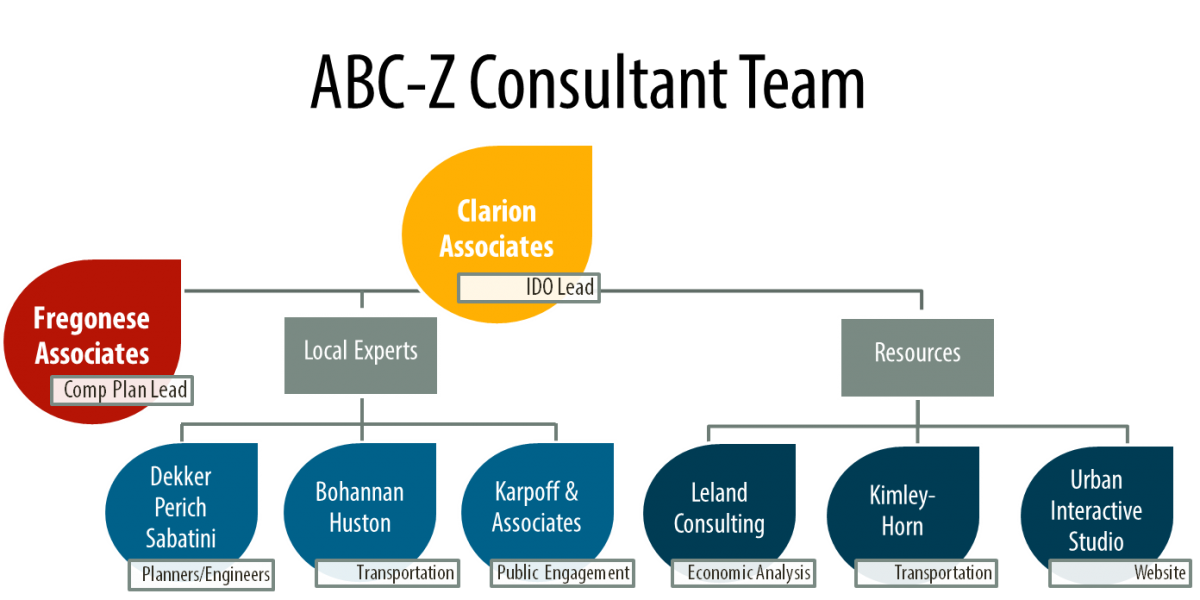

The City hired a consultant team to help with this very ambitious project.

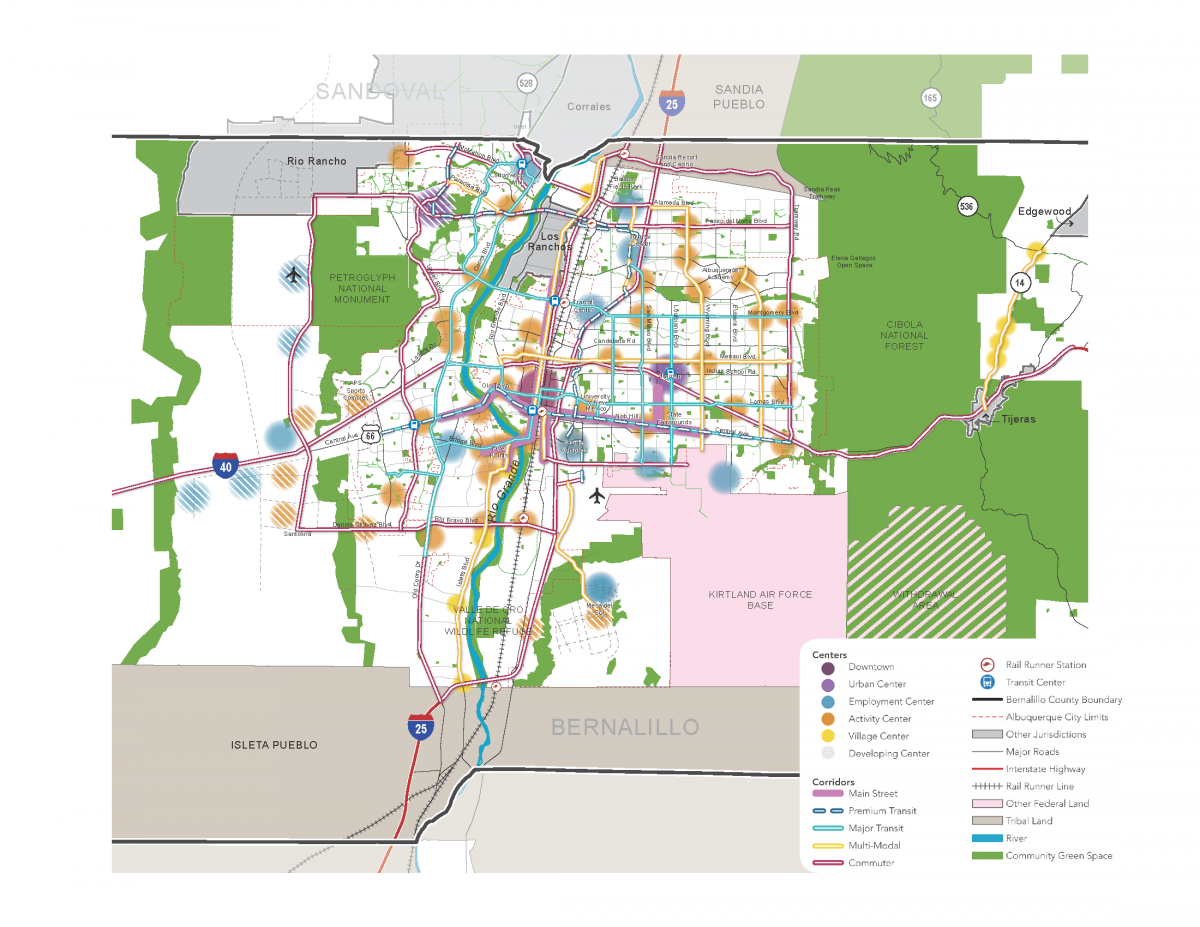

Together with the consultant team, Albuquerque City and Bernalillo County staff worked with residents and other stakeholders to update the Albuquerque-Bernalillo County Comprehensive Plan. The land use and transportation sections were updated to better implement the Centers and Corridors vision, first set out in 2001 and amended in 2012. An extensive outreach effort provided engagement opportunities for residents, property owners, neighborhood associations, business owners, developers communities, advocacy groups, City and County departments, non-profits, and other agencies and institutions.

At the same time, the City project team worked with the consultant team, neighborhood associations and other stakeholders to modernize and update Albuquerque’s zoning, subdivision, and land development regulations to be more user-friendly, incentivize development where the Comp Plan encourages growth, protect established neighborhoods, consolidate and simplify special-use zoning, ensure high-quality development, provide more predictable standards and review/approval processes, and promote Albuquerque’s economic growth.

Simplifying the System

As part of this process, the City integrated policies from adopted Rank 2 Area Plans and Rank 3 Sector Development Plans into the Rank 1 Comprehensive Plan, and eliminated overlapping and repetitive policies and regulations.

In addition, this project analyzed adopted regulations to determine whether they were still relevant, extended good ideas and strategies citywide, and consolidated similar zone districts.

Project Goals

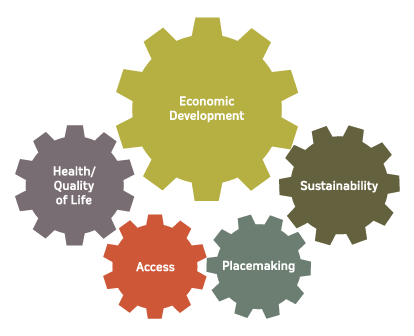

Key goals of the project were to improve the local economy, protect the city’s established neighborhoods, streamline the city’s development review and decision procedures, and respond to water and traffic challenges by promoting more sustainable development. To leverage progress toward these goals, the project team kept in mind these related factors:

1. Economic Development: Improving opportunities for growing local businesses, leveraging cultural activity, creating jobs, and attracting and keeping young workers.

2. Placemaking: Creating vibrant, walkable centers; enhancing special places; attracting employers to activity centers; and ensuring better access for everyone.

3. Access/Mobility: Ensuring the mobility and safety of all users in all areas of the region and supporting land uses.

4. Health/Quality of Life: Providing equitable access to goods and services for all residents; ensuring housing options at all stages of life; enhancing access to healthy recreational areas, including parks and open space areas; encouraging vibrant activity in public places; and supporting economic activity that provides options for meaningful employment with livable wages.

5. Sustainability: Establishing a diverse economy, matching economic activity with available resources; preserving rural, recreational, and open space areas; conserving water resources; and improving alternative transportation options.

Public Engagement

“ABC to Z” included extensive outreach embracing community-wide participation of code users, neighborhood associations, residents, investors, property owners, interest groups, and other stakeholders. Numerous meetings, workshops, and public hearings were held over three years.

The project kicked off with a series of meetings with citizens, stakeholders, and zoning code users in February 2015.

To get up to speed on what's already happened, you can review adopted documents and information on this website!

- The ABC-Z project had many public engagement opportunities between the kickoff in February 2015 and 2018, including visioning workshops, focus groups, meetings, surveys, and community events.

- Public engagement for the Comprehensive Plan

- Public meetings were held for each milestone draft of the IDO.

- A full list of ABC-Z meetings from 2015 - November 2017 is available here.

- The project team offered many IDO trainings between November and May of 2018.

- For a year following the effective date of the IDO, there was a follow-up zone conversion process for those property owners who wanted to change their zoning to match their existing land use(s) with the right IDO zone.

- In October 2019, planning staff met with stakeholders to design the new Community Planning Area (CPA) assessment process, develop outreach plans, and begin baseline analyses.

- In June 2020, City Council decided the order of the CPA assessments based on a priority needs analysis.

- Long Range Planning staff in the Planning Department began engaging community members, businesses, and community organizations through Community Planning Area assessments.

Sign up for email updates or submit comments online

Enter your name and email address here to receive the most up-to-date information about upcoming trainings and involvement opportunities

Call or e-mail project planners

- Mikaela Renz-Whitmore, CABQ Planning Dept., mrenz@cabq.gov or 505-924-3932

- Shanna Schultz, Council Services Dept., smschultz@cabq.gov or 505-768-3185

- Catherine VerEecke, BernCo Planning & Development Services Dept., cvereecke@bernco.gov or 505-314-0387

- ABC-Z Project Team: abctoz@cabq.gov

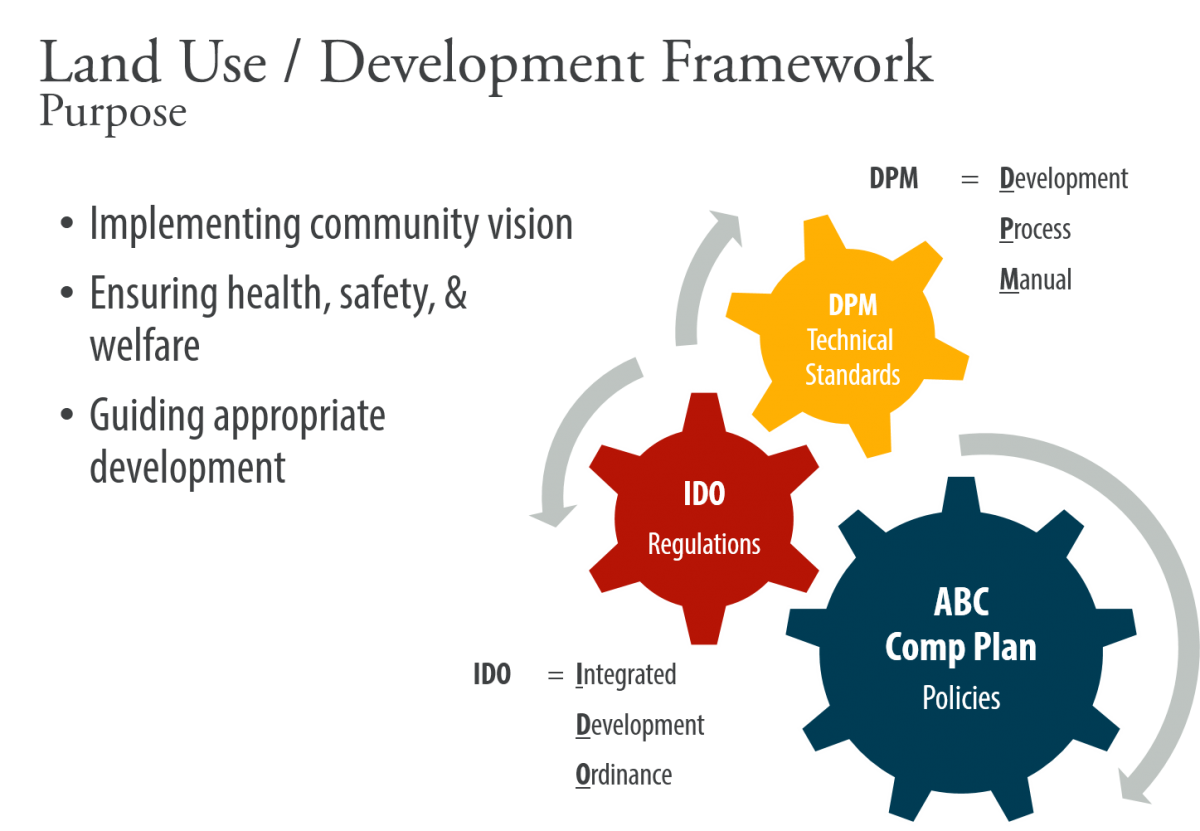

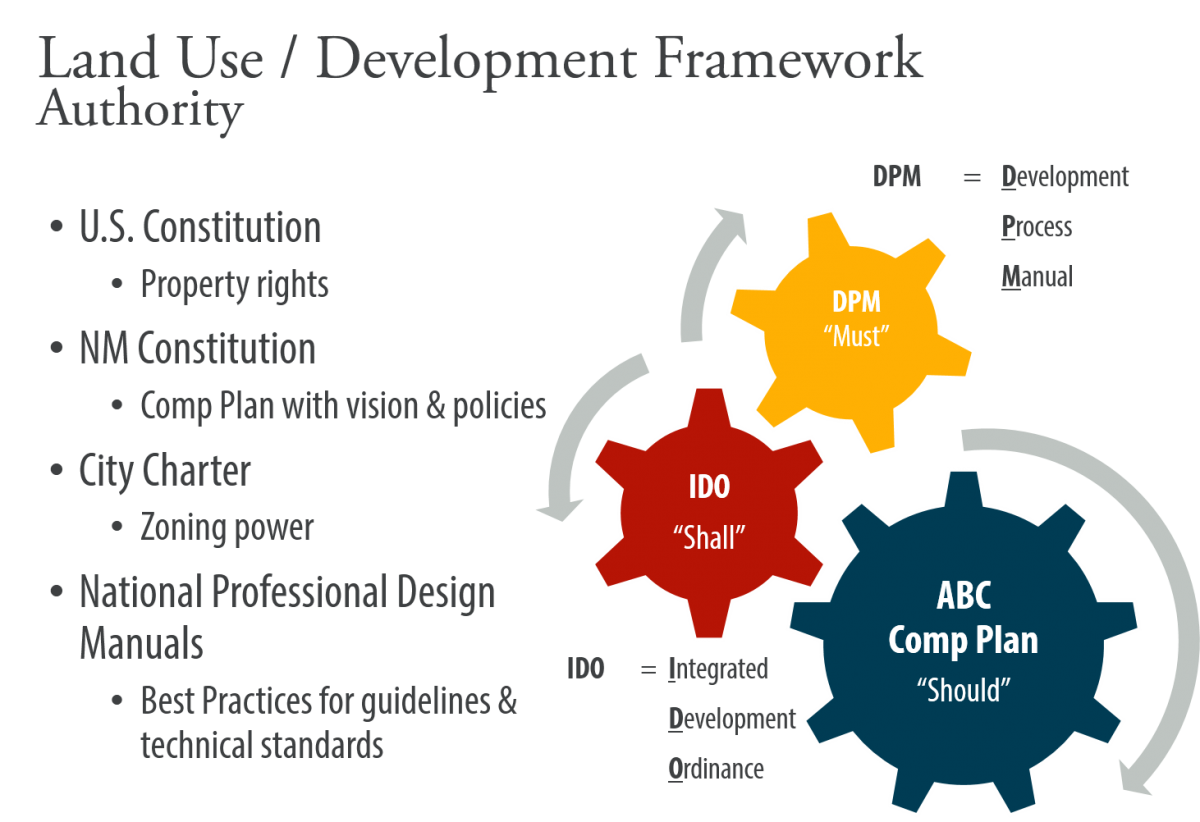

One purpose of a comprehensive plan is to inform the zoning code: the zoning code is the regulatory tool (i.e. "the teeth") used to implement the vision and goals from the comprehensive plan that apply to land use and development.

In other words, a comprehensive plan contains the vision, goals, and policies for growth and development, and the zoning code contains the regulations to implement that vision.

A comprehensive plan is generally not used in day-to-day decision-making for projects that have established zoning, while the Zoning Code is.

See also:

- FAQs about the Integrated Development Ordinance (which replaced the City's 1970s zoning code)

- 2017 ABC Comp Plan

- Integrated Development Ordinance

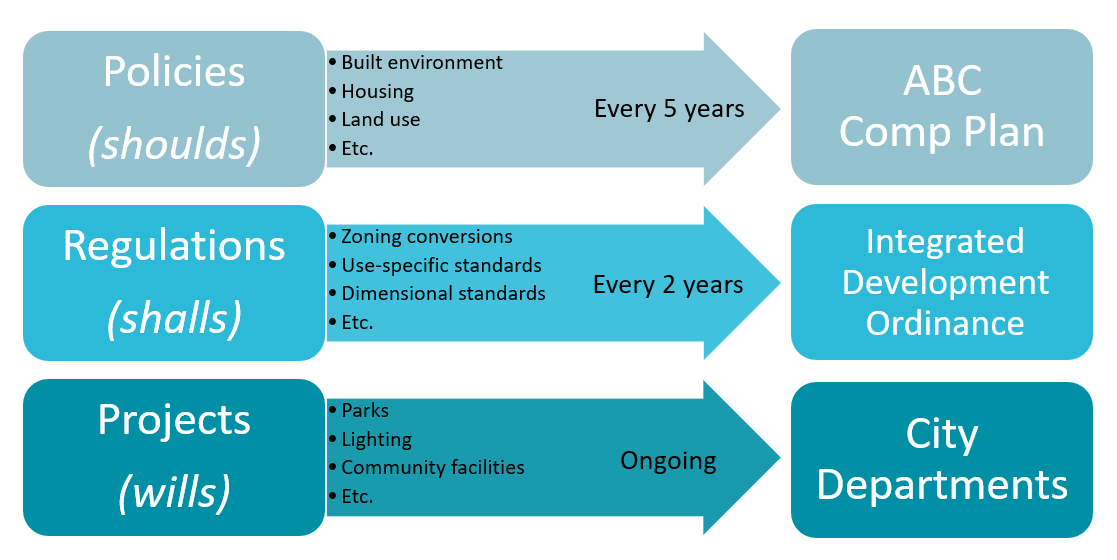

Policies are guidance adopted by organizations to achieve their aims and goals. The City generally adopts policies by resolution.

The Comprehensive Plan is the City’s adopted set of policies related to land use and development, including a community vision for future growth and development. The advantage of policies is the ability to make aspirational goals that may not be enforceable in every instance but set a desired direction that can guide individual actions and decisions.

Policies are used to inform rulemaking and other discretionary decision-making such as zone changes. There may be multiple and competing policies that apply to a particular project or development, and it is up to the decision-making body to determine the relative importance of the relevant policies and decide how best to achieve the city’s community vision and goals.

Regulations are laws adopted to implement policies. The City generally adopts regulations by ordinance.

A regulation has the effect of a law and sets restrictions that are enforced by relevant authorities. Unlike policies, regulations are not aspirational but required in every instance, unless a process for granting an exception under prescribed criteria is provided. Regulations are restrictive in nature and impose sanctions for non-compliance. Policies encourage or discourage certain actions (“shoulds”); regulations require certain actions (“shalls”).

The Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO) is the collection of the City’s adopted laws related to land use and development, and it is intended to implement the City’s Comprehensive Plan vision, policies, and goals. The Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO) consolidated and updated the City’s regulations from the Zoning Code, Subdivision Ordinance, Airport Zoning Ordinance, Landmarks and Urban Conservation Ordinance, and approximately 40 adopted Sector Development Plans that include regulations. Regulations must be clearly written and be enforceable, with objective standards that do not require discretionary judgment or interpretation. The City and private developers must adhere to the adopted regulations, unless a deviation or exception is approved pursuant to criteria in the adopted regulations.

Design guidelines are a set of best practices for designers and engineers and may be created by the City, professional associations, or federal agencies. These are not official policies or regulations, because there are always unique situations and a variety of goals and objectives for each capital project. A professional engineer or architect takes ultimate responsibility for the project design, which is why they tend to rely on established and commonly accepted design practices.

The City uses the term “standard” to apply to technical and design requirements. Standards related to land use and development are consolidated in the Development Process Manual (DPM). This document contains specific requirements for pavement design, road geometry, lane widths, drainage calculations and other similar standards that are used by professional engineers to design a capital project or private development.

Some nationally accepted design guidelines and standards have been “adopted by reference” through Plans, Ordinances, and the DPM. These guidelines must be followed to the extent practicable, and the standards must be followed unless a variance is granted. The process of adopting guidelines and standards by reference allows the City to follow the most updated practices, as amended by the organization that created them. If the guidelines and standards were adopted in whole by a local government, then each time new standards are created or updated, the local government would have to amend their version of the same rules.

No, Bernalillo County did not change their zoning or Sector Development Plans as a result of this project.

Step-By-Step Guides

The guides below will walk you through finding key pieces of information for your property or the land use you are interested in, and then direct you to the parts of the IDO that provide answers.

- What uses can be developed on a property?

- Where in the city can I develop a particular use?

- What are the development standards for my property?

- What review or approval process will I need to go through?

Looking up Your Zone

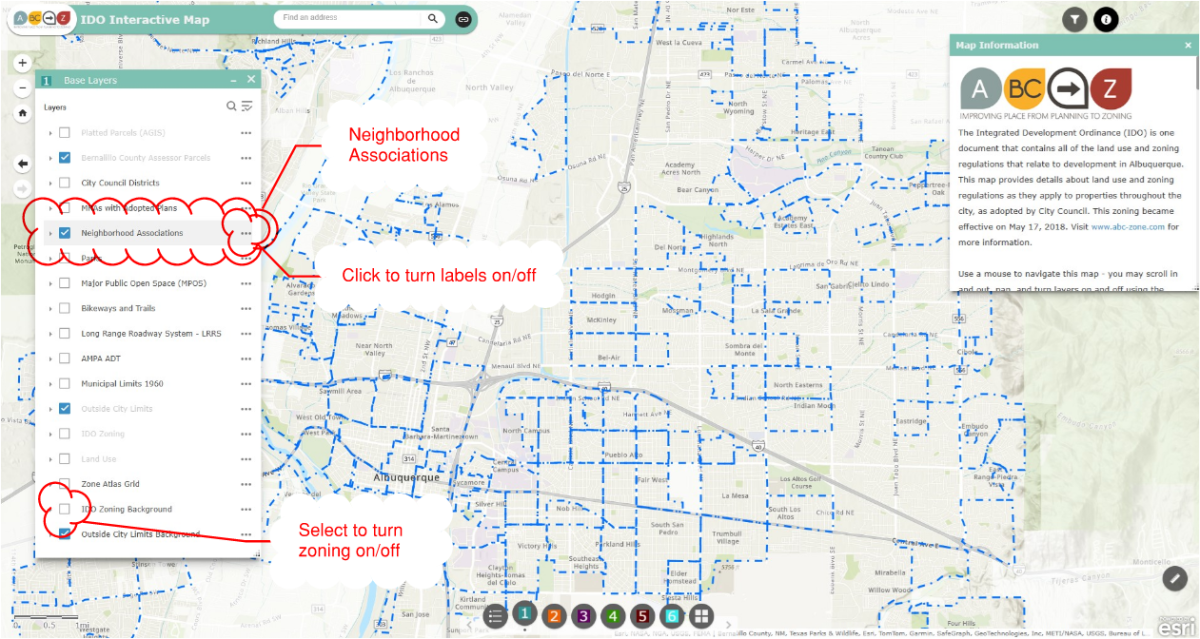

Enter your address in the IDO Zone Look-up Map in the search bar at the top of the map. Your property will be shown with a black dot. Click on the property. A pop-up window with information will appear on the right-hand side of the map. Click the small white arrow at the top of the box to see your zoning category, a link for allowable uses, and your old zoning designation. If you click on the "More Info" link, a new tab will open with the allowable uses in your zone, as shown in Table 4-2-1 of the Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO) .

If you need more information, use either the IDO Interactive Map or the Advanced Map Viewer.

Looking up Your Allowable Uses

Once you know the zone district for your property, you can look at the Use Table from the Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO) to see the uses that are allowed in your zone.

Table 4-2-1: Allowable Uses makes it easy to see what uses are allowed in each zone.

Be sure to check the IDO to see if there are any Use-specific Standards that may expand or limit the use in certain zones or in proximity to other zones or uses.

See also:

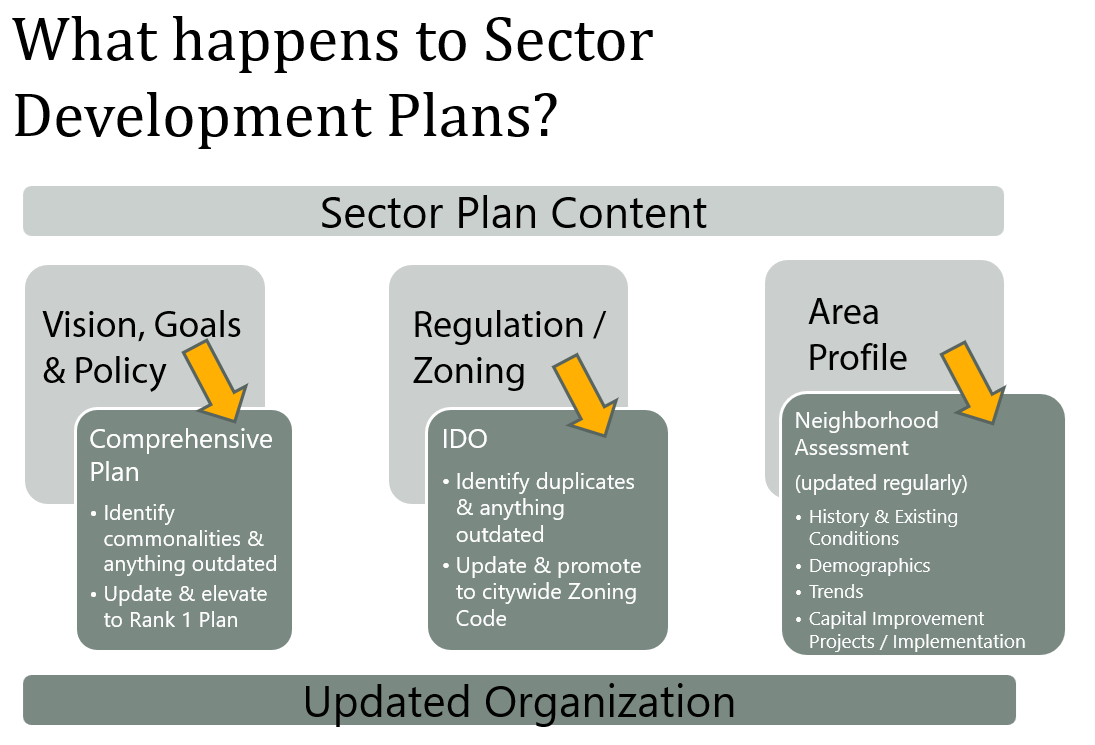

From the 1970s to 2013, over 60 Sector Development Plans were crafted over months and years, with much input, engagement, passion, and energy from local residents and businesses. Many of these plans included policies and regulations intended to protect and enhance neighborhoods and special places.

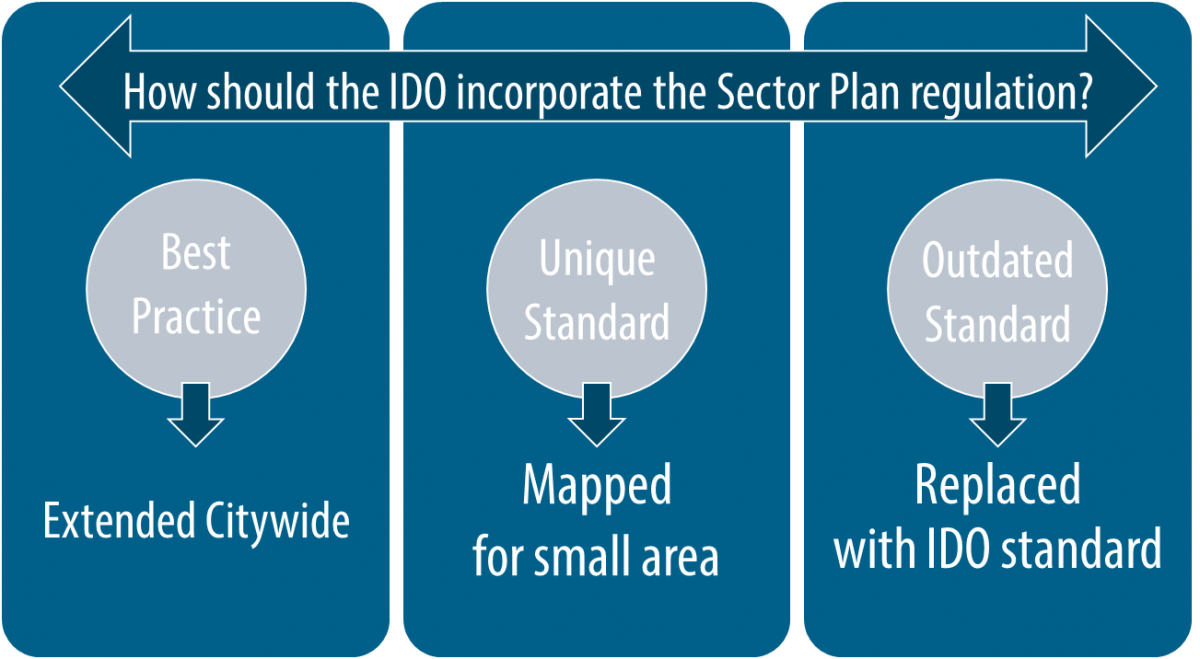

Clarion Associates is a firm that was hired to help write the Integrated Development Ordinance because of their expertise in writing city-wide Development Ordinances. The firm emphasized that our old regulatory system – comprised of the Comprehensive Zoning Code and more than 40 Sector Development Plans that also established special zoning in discrete areas – was one of the most complex it had ever seen after working in over 130 cities. The process of mixing area-specific comprehensive planning (policy guidance) and zoning in standalone Sector Development Plans outside a city-wide zoning code is not a national best practice. It often leads to confusion about the rules of development and inconsistencies in interpretation and enforcement. One of the key goals of this effort was to simplify and consolidate our system of regulations, while still prioritizing effective protections for our neighborhoods and special places.

Clarion Associates made the following recommendations in 2015:

- The City needs to replace the existing system of sector development plans and discrete zoning with one that clearly distinguishes between planning advice (policy) and zoning regulations (regulations) for specific areas and provides more effective protection for special places and neighborhoods.

- The city needs to absorb the best policies for protecting and enhancing community character in the Sector Development Plans into the Comprehensive Plan, and needs to include the best area-specific regulations into the Integrated Development Ordinance, where they can be better monitored and enforced.

- Many of the ideas for preserving character and quality in the current Sector Development Plans are very similar, and can be turned into general standards applicable to similar development throughout the city without weakening any of the current negotiated standards.

- For unique areas, it may be necessary to create area-specific development overlays or regulatory controls, but this will be the exception rather than the norm.

The content of Sector Development Plans that was still relevant, effective, and representative of a neighborhood's vision for future development was retained by carrying it into the updated Comprehensive Plan (goals and policies); the IDO (regulations), where it can be better understood, monitored, and enforced; or as a historical document in Appendix D of the Comprehensive Plan to inform the Community Planning Area Assessments.

Read more in this 5-page handout.

See also:

- Where can I find regulations from my Sector Development Plan that apply to my area in the IDO?

- How does ABC-Z propose to improve public engagement with the City?

Many regulations that have been effective in achieving the community's vision and goals were carried over into standards for zone districts in the IDO, such as R-1 - and made available to other neighborhoods with similar characteristics, goals, and challenges. Many neighborhoods currently not covered by a sector plan will now benefit from additional protections available in SU-2 zones.

Some SU-2 zones were found to be outdated, ineffective, or unenforceable. In this case, best-practice standards for base zoning districts in the IDO offer better or more effective protection for neighborhood areas.

In other circumstances, individual regulations important to preserving or enhancing character were carried into an overlay zone or as a mapped area with unique regulations.

The drafting process of the IDO allowed multiple opportunities for communities and stakeholders to help decide which tools to use to carry over important provisions from adopted SU-2 regulations.

See also:

- Presentation: Comparing Sector Plan System with IDO System of Small Area Protections

- Handout: Comparing pre-IDO zoning to IDO zoning

- Where can I find the specific regulations from my Sector Development Plan that apply to my area?

- What regulations from my Sector Development Plan were extended citywide?

The City has adopted several Arroyo Corridor Plans as Rank 3 Plans. Under the old system (prior to the Integrated Development Ordinance or "IDO"), some of these plans had regulations (such as zoning regulations) that applied to private property developed next to these arroyos. Those regulations were moved into the IDO when it was adopted in 2017, and the adopting legislation (O-17-49) changed the status of the Arroyo Corridor Plans to be Resource Management Plans with policies that guide the maintenance of arroyos.

Summaries of Arroyo Corridor Plans with regulations that moved to the IDO:

Resource Management Plans:

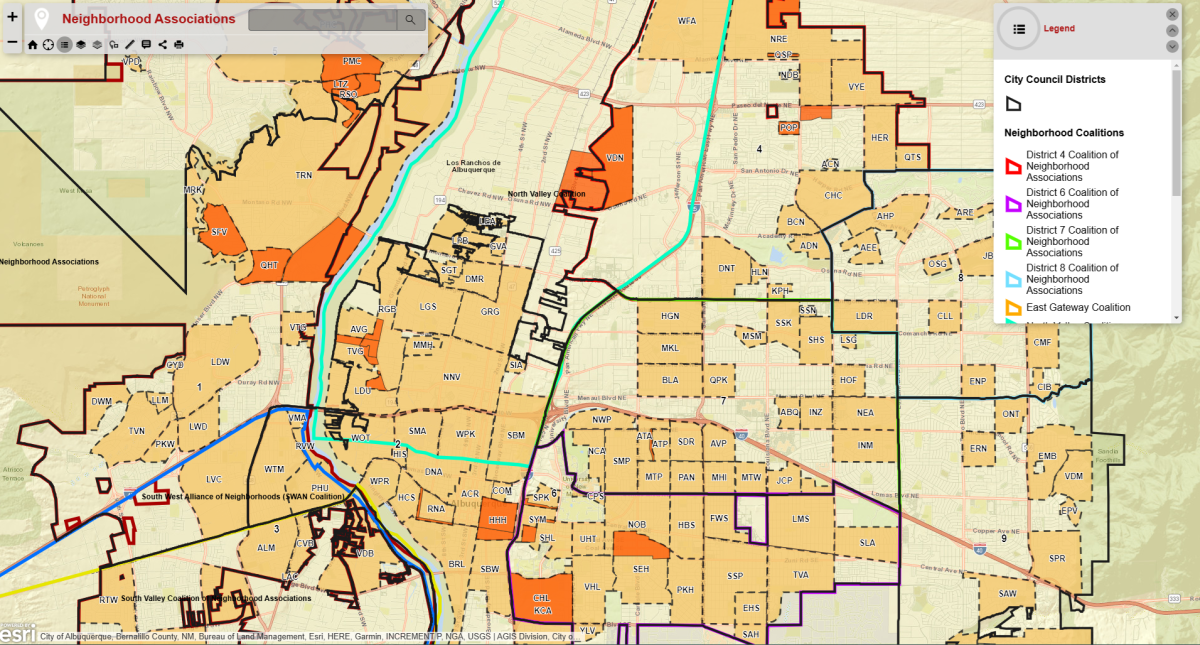

Absolutely not! The City's Neighborhood Association Recognition Ordinance (sometimes referred to as "NARO") the Office of Neighborhood Coordination will continue to serve as a liaison among City departments, Council, and neighborhoods.

Neighborhood Associations still register with the Office of Neighborhood Coordination to receive notice of certain development proposals within their boundaries.

See an Interactive Map of Recognized Neighborhood Associations here.

ABC-Z included several proposals to improve public engagement with the City:

- Community Planning Area Assessment Process: The City proposed to shift the emphasis from creating Sector Plans (to address crises in a particular neighborhood) to a proactive process of working with ALL areas of the City on a rolling, 5-year cycle. This process is outlined in the Community Identity chapter in the updated Comp Plan and is codified in Module 3 of the IDO.

- Civic Leadership Academy: The City hosts an annual series of workshops for residents, property owners, decision-makers, business owners, and others to understand our land use and development process - including the Comprehensive Plan, the IDO, and other processes for City projects. These sessions can include discussions of the protections built into the IDO to protect neighborhoods as well as the "levers of opportunity" that neighborhood associations have to affect development projects.

- Office of Neighborhood Coordination: Together with Long Range Planning staff, ONC can coordinate with neighborhood associations and other stakeholders in planning efforts, City projects, and the Civic Leadership Academy.

See also:

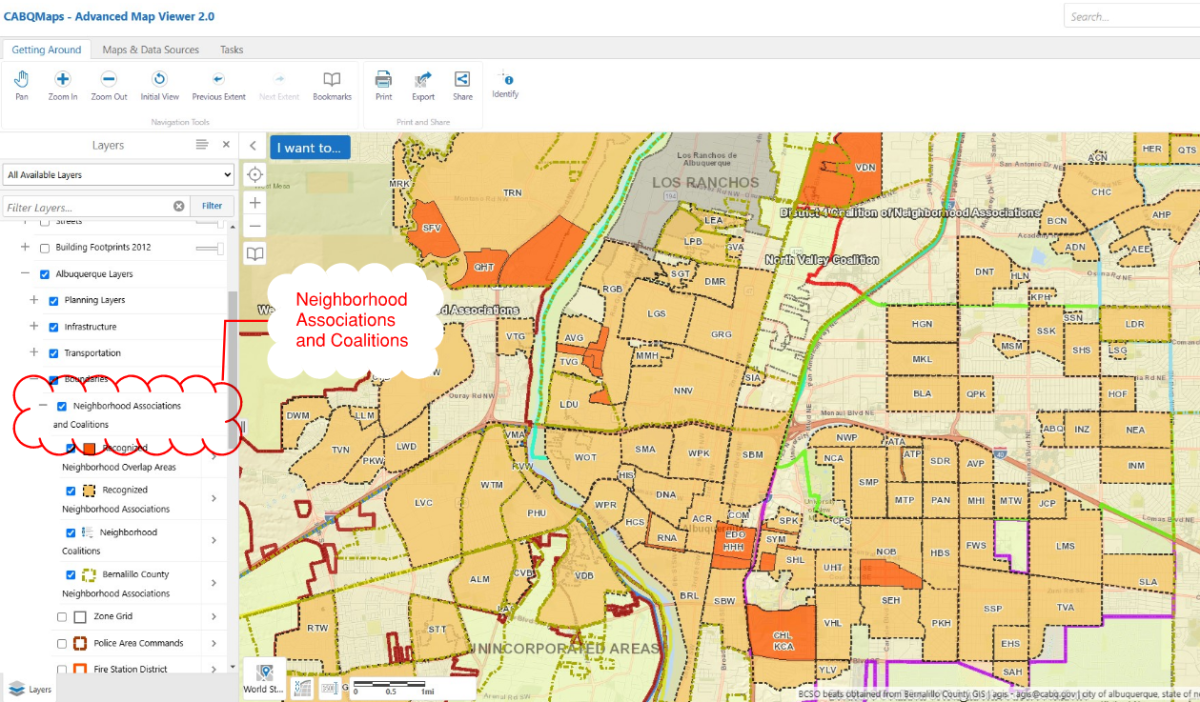

There are several ways. Three online maps below let you look up your Neighborhood Association by geography. You can also find links to Neighborhood Association websites on the Office of Neighborhood Association webpage.

If you only want to see Neighborhood Associations, this is the map for you! Interactive Map of Recognized Neighborhood Associations.

Neighborhood Associations are also one of many layers of information you can turn on via the IDO Interactive Map or the AGIS Advanced Map Viewer.

- Community Planning Area Assessment Process: ABC-Z shifted the City's approach to long-range planning to a proactive process of working with ALL areas of the City on a rolling, 5-year cycle. The City's Long Range team will spend time in each Community Planning Area to gather data, inventory assets, and create an action plan for each Community Planning Area. Recommendations from those assessments will also be rolled into the bi-annual update of the Integrated Development Ordinance and the 5-year update of the Comprehensive Plan.

- City Leaders Academy: The Planning Department hosts a regular series of workshops for residents, property owners, decision-makers, business owners, and others to understand our land use and development process - including the Comprehensive Plan, the Integrated Development Ordinance, and other processes for City projects. These sessions will include discussion of zoning protections built into the IDO to protect neighborhoods, as well as the "levers of opportunity" that stakeholders have to affect development projects.

- Office of Neighborhood Coordination: The Office of Neighborhood Coordination is part of Council Services. We share a commitment to improve responsiveness to neighborhood associations and other stakeholders in planning efforts, City projects, and the City Leaders Academy.

For more information:

- Community Planning Area website

- ABC Comprehensive Plan

- Community Identity chapter

- Implementation Chapter Strategy 1 and 4

- Appendix E: How the City Will Plan With Communities In the Future

- Integrated Development Ordinance

See also:

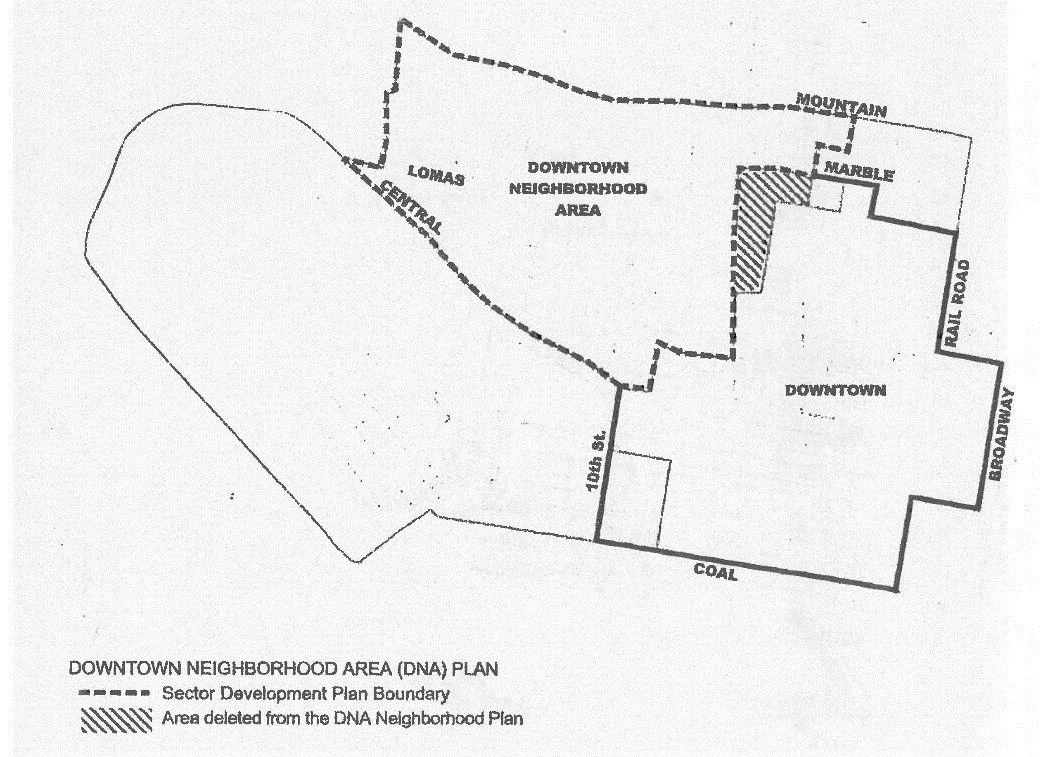

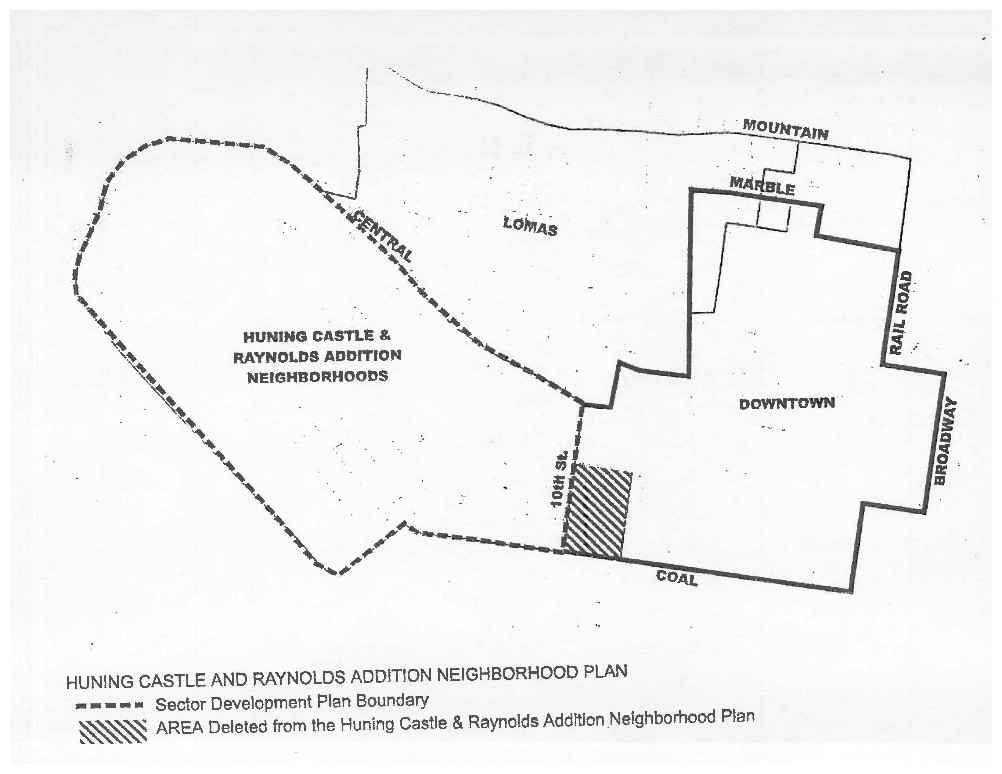

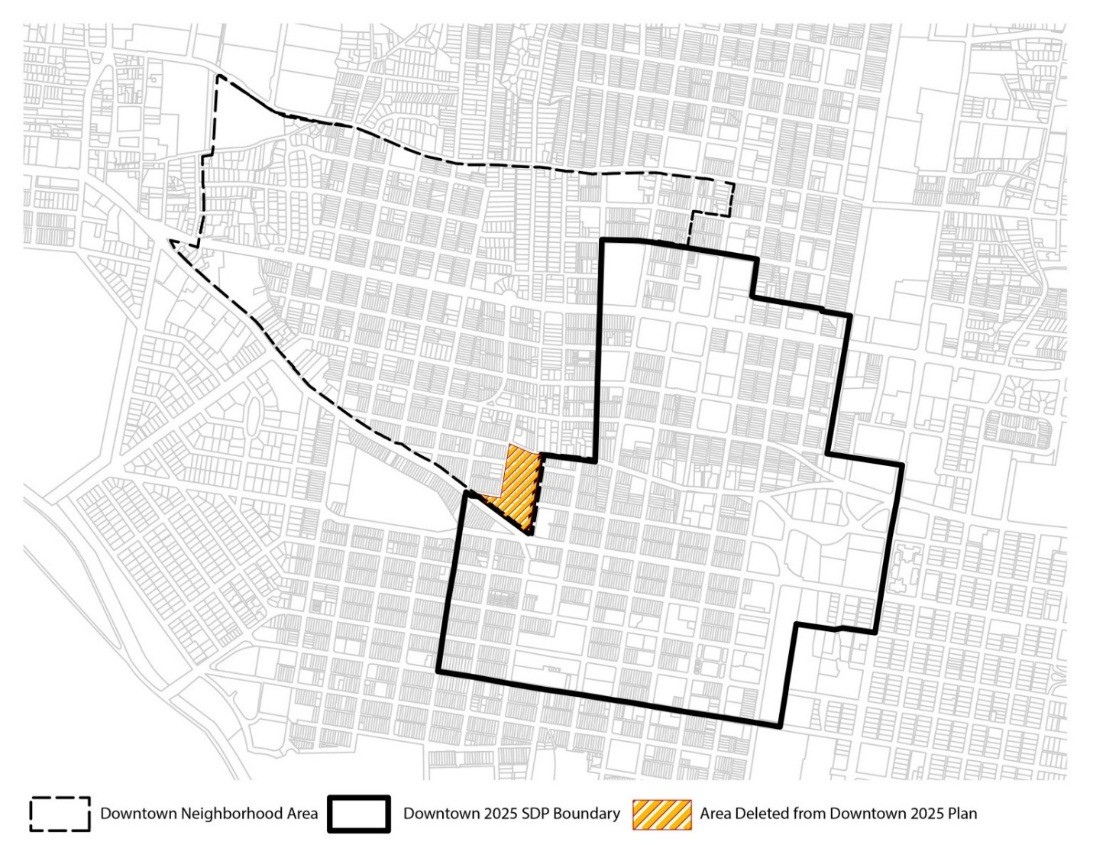

The project team thought the boundary for Downtown was the same in all three documents until we did some sleuthing in July 2017.

It turns out that the boundary for Downtown changed at least twice, and it's currently different in each document as a result of uncoordinated changes over time.

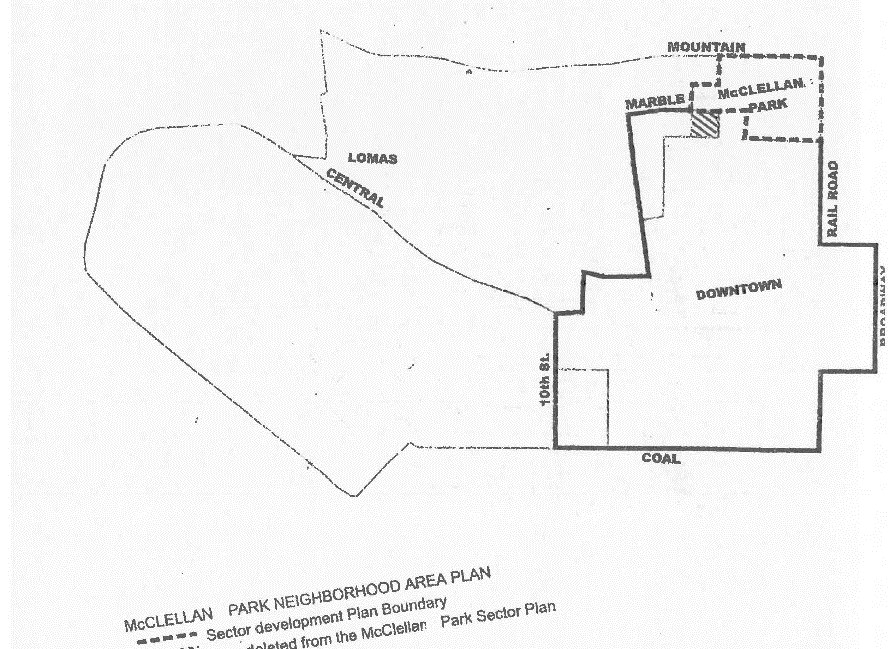

The original adoption of the Downtown 2010 Sector Development Plan in 2000 (R-21-2000, Enactment 50-2000) adjusted the boundaries of the Downtown Neighborhood Area SDP, Huning Castle Raynolds Addition SDP, and McClellan Park SDPs, documented in the Council resolution adopting the Downtown 2010 SDP:

Downtown Neighborhood Area SDP Deleted Area

Huning Castle Raynolds Addition Neighborhood Plan Deleted Area

McClellan Park Neighborhood Area Plan Deleted Area

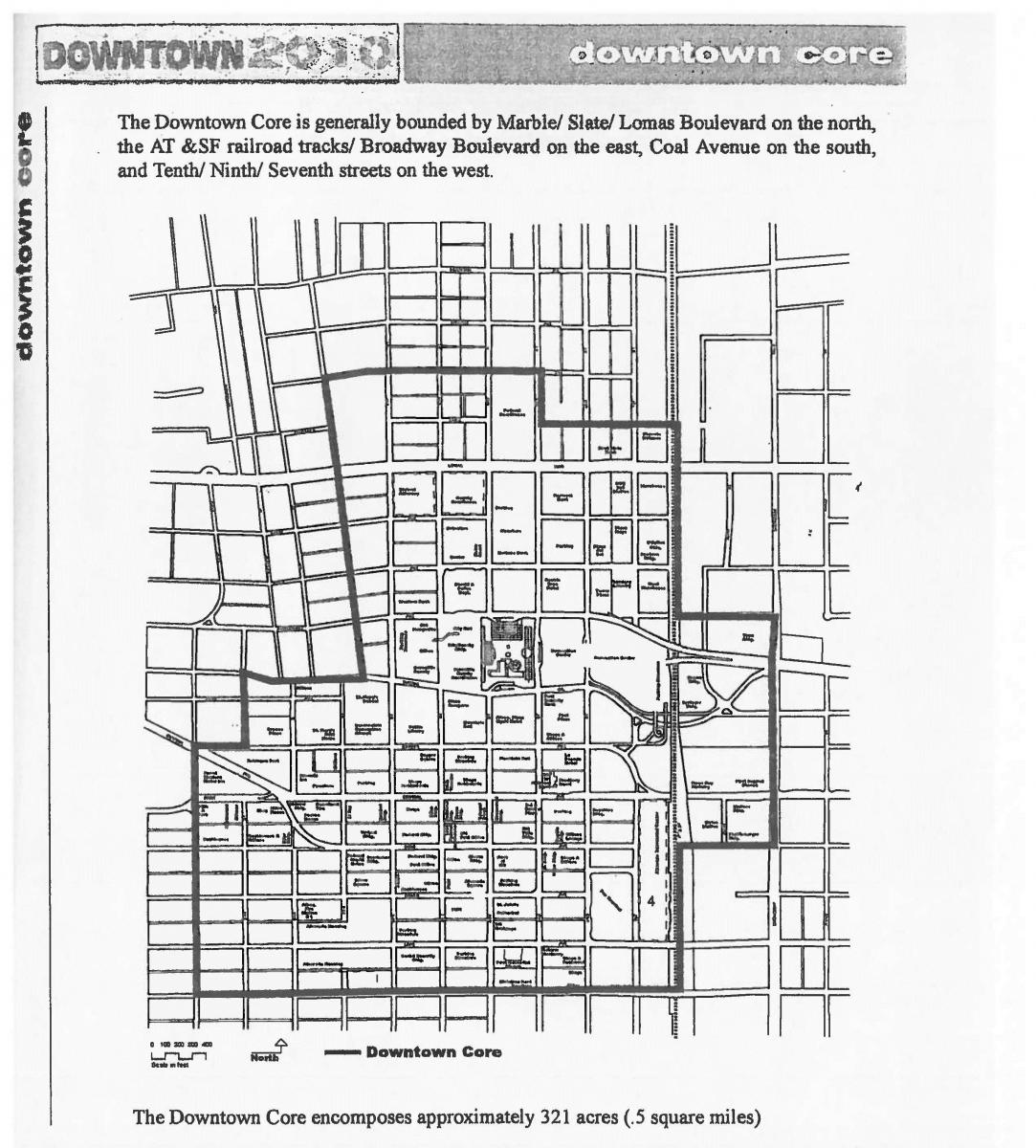

Original Downtown 2010 SDP Boundary from 2000

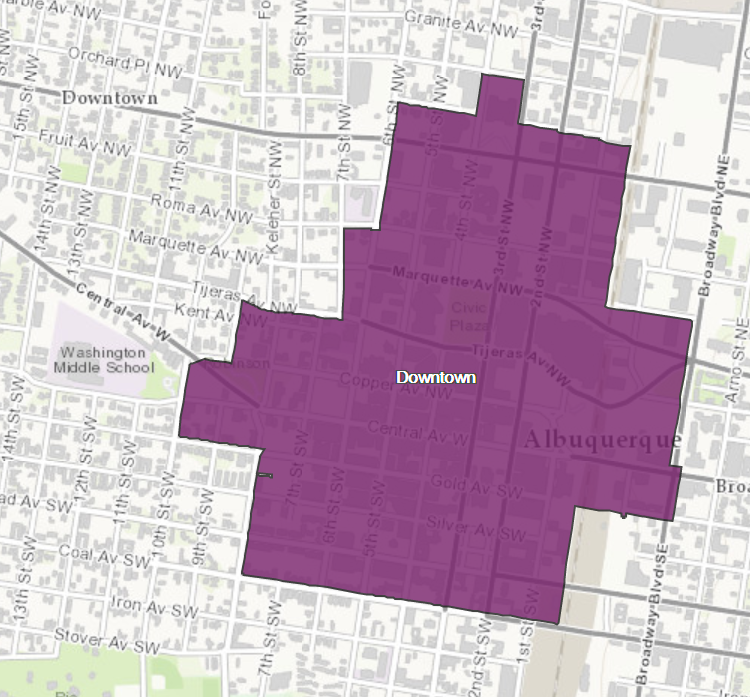

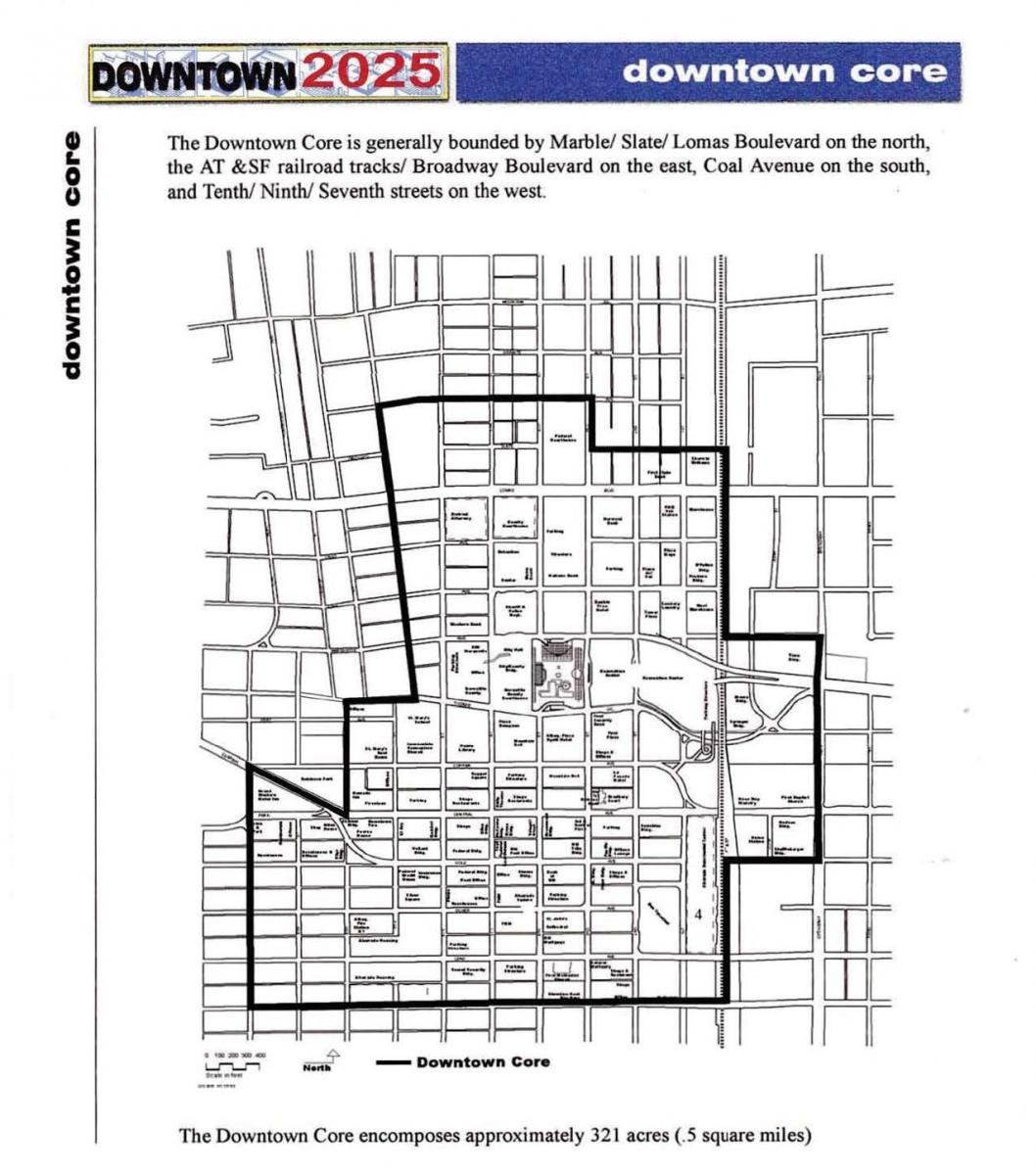

Downtown Center

In 2001, Downtown was designated a Center in the Centers & Corridors amendment to the Comprehensive Plan. The Comprehensive Plan Center is not the same as the Downtown 2010 SDP boundary. For some reason, the areas that had been deleted from adjoining SDPs were not included in the Downtown Center boundary in the Comprehensive Plan. The area excluded from the Downtown Center boundary includes:

- Two blocks between 8th and 10th Streets in the southwest corner (shown as deleted from the Huning Castle Raynolds Addition SDP in the map above)

- One block at 5th and Marble in the north (shown as deleted from the McClellan Park SDP in the map above)

- Four blocks on the northwest corner (shown as deleted from the Downtown Neighborhood Area SDP in the map above)

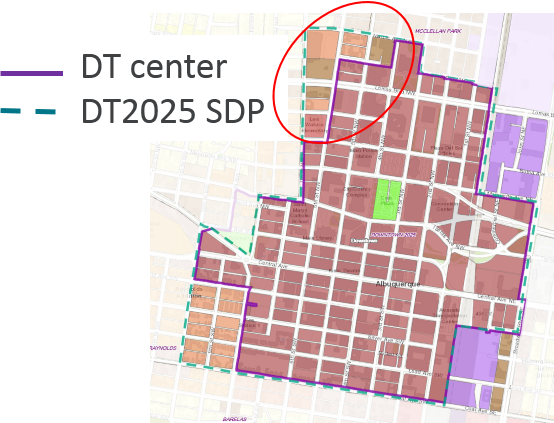

Downtown Center vs. Downtown 2025 SDP Boundary

Downtown Metropolitan Redevelopment Area

In 2003, the Downtown 2010 SDP boundary was adopted as the Metropolitan Redevelopment Area boundary for Downtown (F/S R-03-294, Enactment R-2003-160), and in 2004, the Downtown 2010 SDP was adopted as the Metropolitan Redevelopment Plan for Downtown (R-04-50, Enactment R-2004-044).

In 2012, the Downtown 2010 SDP boundary was changed with the adoption of an updated Downtown Neighborhood Area SDP (F/S R-11-225, Enactment R-2012-052), but this change was not reflected in the Downtown 2010 SDP at that time.

Downtown 2025 SDP

In 2014, the Downtown 2010 SDP was amended, in part to update the name to Downtown 2025 SDP, and the boundary adjustment from 2012 was reflected in the updated document.

Despite these changes to the Downtown boundary in the SDP, neither the Metropolitan Redevelopment Area nor the Comp Plan center boundary for Downtown were amended to reflect the changed boundary for Downtown. The project team has noted these discrepancies and will recommend that they be adjusted to track with the MX-FB-DT zone district in the IDO, which carries over the Downtown 2025 SDP boundary. In the meantime, where the IDO references "DT," the provisions are mapped for the Center as mapped in the 2017 ABC Comprehensive Plan.

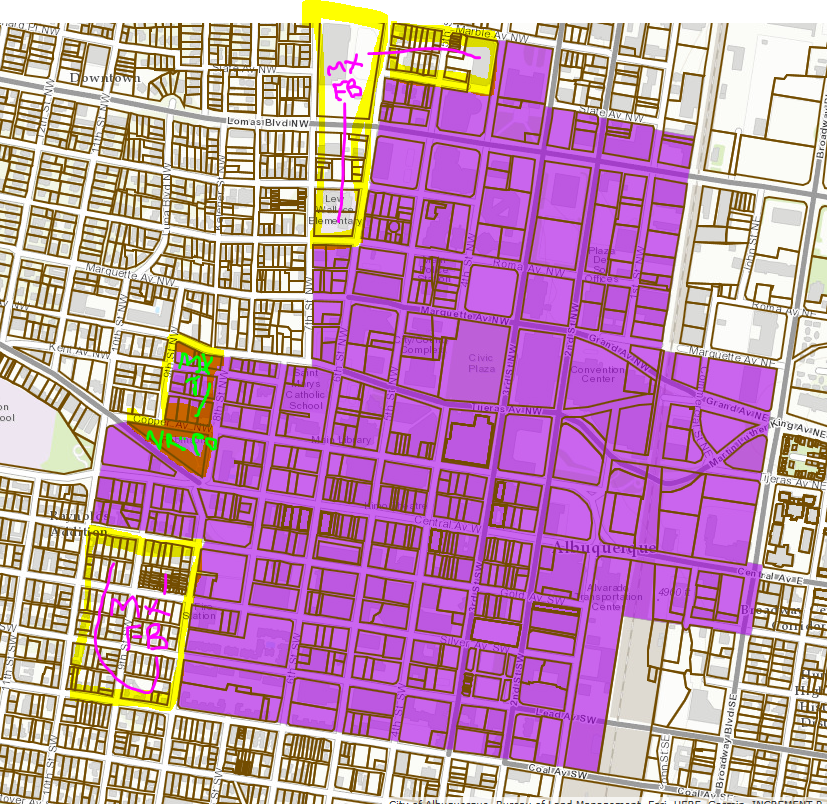

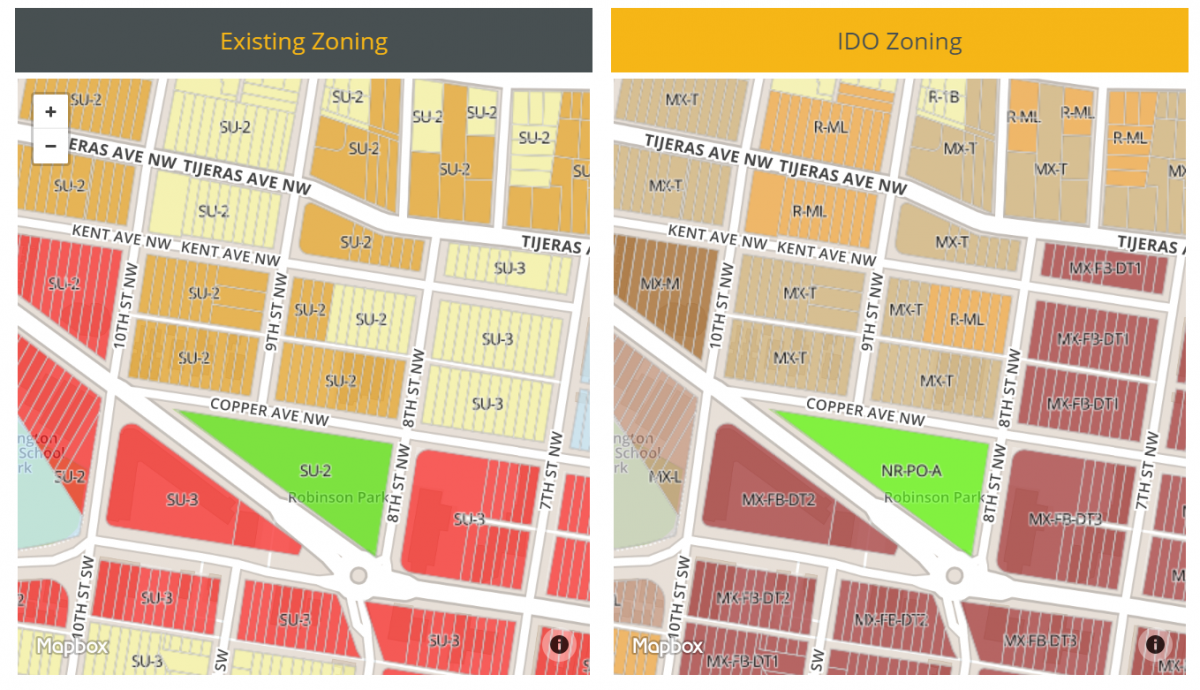

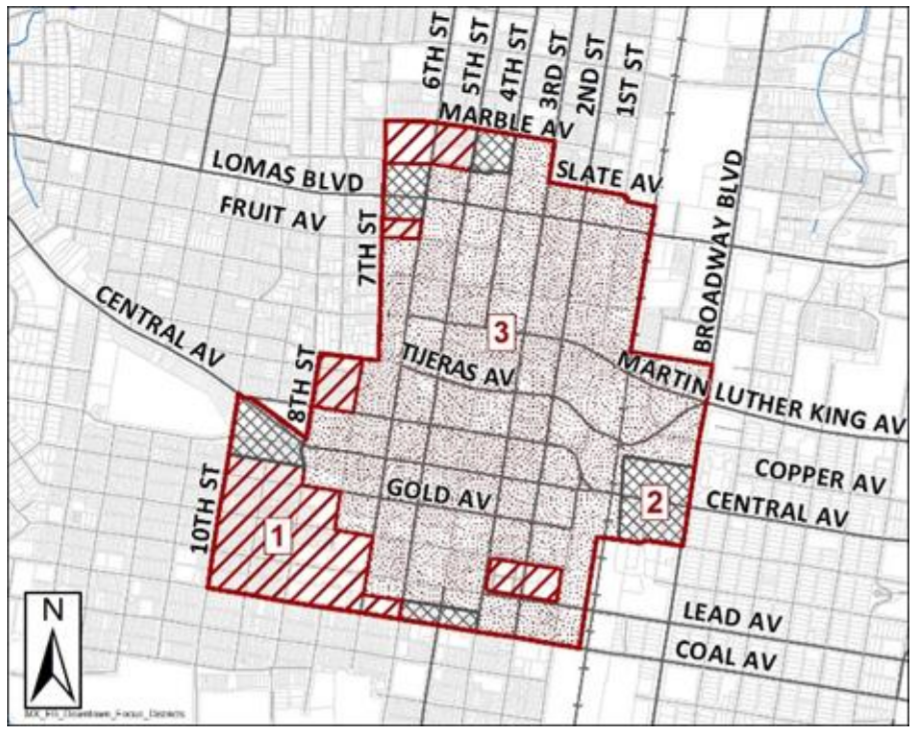

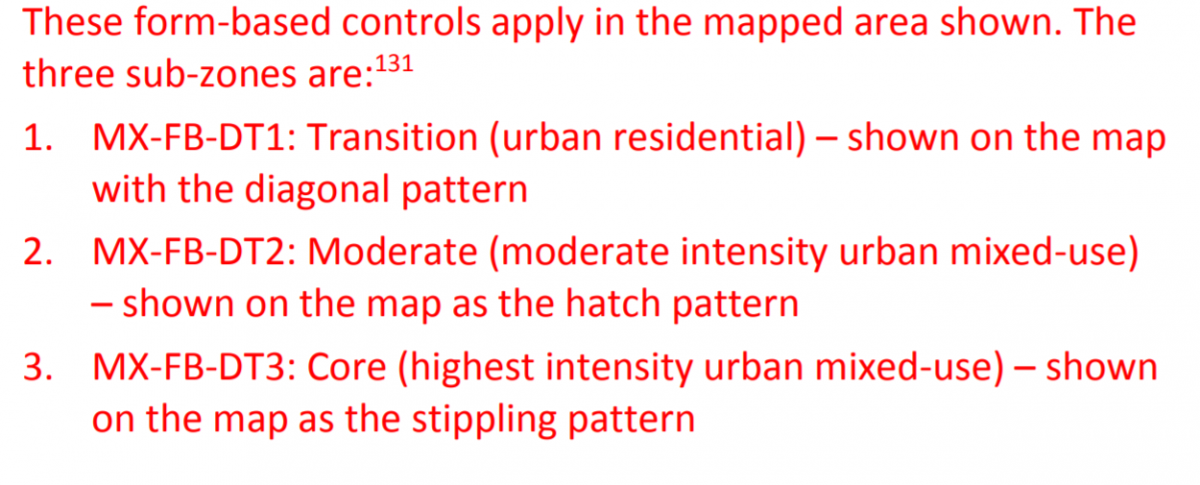

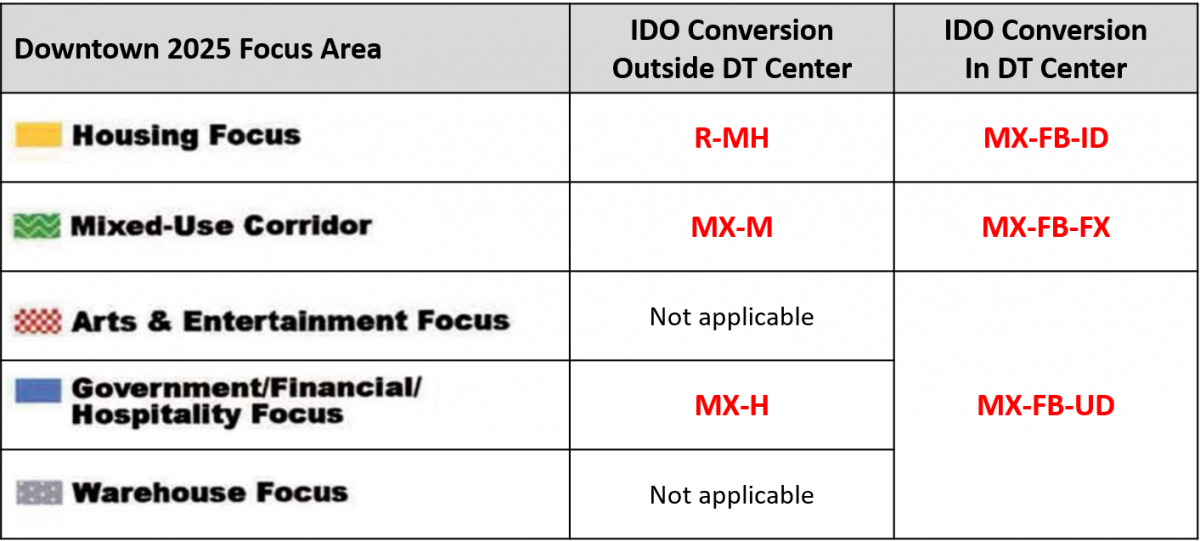

Downtown Center (purple) vs. LUPZ IDO Conversion Map Zoning

- Purple boundary shows the Downtown Center as mapped in the 2017 ABC Comprehensive Plan. The LUPZ version of the zoning conversion map converted all the Downtown 2025 SDP zones into MX-FB-DT, which mapped 3 sub-zones to track with uses and dimensions in the Downtown 2025 SDP.

- The areas with green labels for MX-T and NR-PO-B were deleted from the Downtown 2025 SDP when DNA SDP was amended in 2012, but they remain in the MRA boundary for Downtown and the Comp Plan boundary for the Downtown Center.

- The additional area in the Downtown 2025 SDP is labeled in pink as MX-FB. Those two areas are included in the MRA boundary for Downtown but not in the Downtown Center in the Comp Plan.

Here is a close-up of the zoning near Robinson Park. The zoning outside the Downtown 2025 SDP did not change as a result of the LUPZ Committee Amendment EE, while the parcels showing MX-FB-DT did change (explained below).

Here are the LUPZ Draft of the MX-FB-DT subzones:

Downtown Center (purple boundary) vs. Post-Committee Amendment EE Conversion Map Zoning

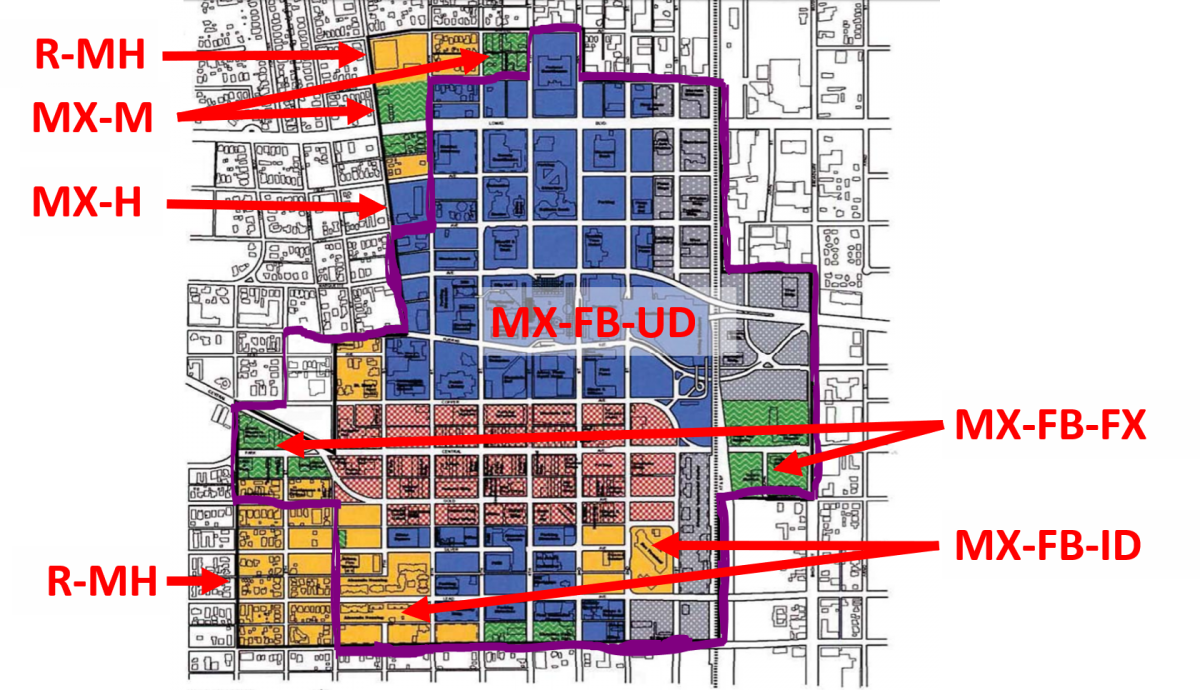

Committee Amendment EE adopted Mixed-use Form-based (MX-FB) subzone into the IDO and mapped all of the Downtown Center that had formerly been an SU-3 zone in the Downtown 2025 SDP as one of the sub-zones. See the map and table below.

The areas outside the Downtown Center that had been part of the Downtown 2025 SDP were converted to a straight zone out of the IDO that most closely matched the

Here's an illustration of the different MX-FB sub-zones.

Downtown Center vs. Metropolitan Redevelopment Area

- All included in Areas of Change with the exception of the two park areas noted as Areas of Consistency for Robinson Park and Civic Plaza.

The Resolution (R-17-213) accompanying the IDO adoption specifies that Metropolitan Redevelopment Area (MRA) Plans that were adopted jointly as Sector Development Plans will continue to remain in place as MRA plans. The project team is hoping to confirm that the MRA boundary for Downtown coincides with the Downtown Center.

Yes!

Fregonese Associates, our consultant for the Comprehensive Plan, created a computer model of Albuquerque’s land use and regulations with a scenario planning software called Envision Tomorrow. They coordinated this modeling effort with the Mid-Region Council of Governments, which incorporated scenario planning into the planning effort for Futures 2040, the long-range transportation plan for our metropolitan region. Futures 2040 adopted – for the first time – a preferred scenario for future growth. This preferred scenario had Centers and Corridors at its heart, and the plan incorporated recommendations to agencies for implementation, as well as a short-term and long-term capital investments needed to realize the preferred scenario for growth. Many of these recommendations were implemented through updates to the 2017 Comprehensive Plan and the IDO.

Both projects aim to reflect the latest thinking in transit services, but are not directly tied together.

The 2001 Comprehensive Plan designated Central Avenue as a Major Transit Corridor, and the ART project attempted to implement those existing adopted policies.

The 2017 Comprehensive Plan designates Central Avenue as a Premium Transit Corridor (which makes high-capacity transit such as Bus Rapid Transit appropriate for the corridor) and includes policies to encourage growth and transit-oriented development along the corridor.

Central is also designated by the Mid Region Council of Government's Long Range Transportation System Guide as part of the Priority Investment Transit Network. One of the purposes of the Comprehensive Plan Update was to coordinate with and help implement the regional Metropolitan Transportation Plan and achieve the benefits of the preferred scenario that it adopted.

For more on the Albuquerque Rapid Transit project for Central Ave, please visit: https://www.cabq.gov/transit/services/art-information

What is a Premium Transit Corridor?

How are transit stations identified for a Premium Transit Corridor?

Why does the IDO allow taller buildings and require less parking along Premium Transit Corridors?

How will ABC-Z protect the character of Nob Hill within the Central Ave Premium Transit Corridor?

Access-control policies for Coors will remain in place, as will the existing view protections. The Integrated Development Ordinance implemented the design overlay zone from the adopted Coors Corridor Plan as a View Protection Overlay. Other development regulations from the Coors Corridor Plan were brought into the IDO as a Character Protection Overlay.

The ABC Comprehensive Plan adopted was in March 2017 and removed the Premium Transit designation for Coors Boulevard.

Albuquerque's economic development horizon still shows.

Due to limited growth in employment, the 2017 ABC Comprehensive Plan revised the types of Centers to downgrade many to Activity Centers, which are less urban, less mixed-use, and less walkable than the Urban Centers. This was done because saying all Corridors will grow is probably unrealistic and may dilute growth in such a way that would prevent establishing real mixed-use, pedestrian places where most appropriate. The 2017 Comprehensive Plan designates two truly Urban Centers - Uptown on the east side of the river and Volcano Heights on the West Side. The 2017 Comprehensive Plan also created a new designation for Employment Centers, where the emphasis for new development will be jobs, services, and retail.

The Integrated Development Ordinance contains different conversion rules for areas east versus west of the river to ensure opportunities for non-residential development (job centers, retail, and services) on the West Side. On the West Side, where there is a heavy imbalance of jobs and housing, C-2 property is proposed to convert to NR-C, a non-residential commercial zone. See more details about zoning conversion decision-making rules here.

If a property has zoning, the property owner is entitled to build at the density allowed by that zone. Local government cannot legally stop people from developing their property when they have the entitlements, unless the government buys it from them at fair market price or passes a moratorium on growth. Even if a moratorium or growth boundary could be passed politically, these come with their own set of challenges, such as affordability issues when property values rise, which can ultimately lead to displacement.

Within the Comprehensive Plan, areas designated as "Reserve" Development Areas in the County are intended to ensure that development that does happen on our edges, or that it does so as a master-planned community, with a balance of jobs and housing, necessary infrastructure to support growth, and a development form that is better for the larger community and more sustainable than low density residential-only sprawl.

As for development inside our urban footprint, it is often very challenging to develop infill sites. Neighbors are often uncomfortable with proposed changes. Small sites often struggle to meet development standards that are often written for larger, greenfield sites without the constraints that smaller infill sites have. Among other development constraints, utilities often need upgrades or costly repairs. Sometimes the location or size of vacant land is not conducive to particular kinds of new development.

The bigger issue is not so much about vacant land as it is about under-developed or outdated development. Until there is a good reason to do so, many property owners do not redevelop. Local government has to find ways to make it more financially desirable to redevelop than to continue with existing rents. In the Comprehensive Plan and through regulations, we look for ways to direct / encourage / incentivize growth where the Comprehensive Plan says it is desirable (such as in Areas of Change).

Direct public investment in infrastructure, community facilities, and parks or open space is the best way, but there are always limited funds and many competing political priorities.

Population density is the number of people living in a certain area. The built environment affects density based on how close residences are to each other and to other uses, such as services, employment, recreation, and schools. In general, the growth strategy in the City's Comprehensive Plan is to encourage growth in areas already served by services, schools, community facilities, employment centers, and transit to leverage these investments for the most people. This community vision is the Centers & Corridors strategy for growth.

The City's zoning code, the Integrated Development Ordinance, creates incentives and design requirements to implement the Centers & Corridors strategy.

How density looks varies a lot! Many different factors affect the density of any particular housing development.

- Different housing types create different densities. For example, on 10 acres of land, single-family homes on individual lots will often result in less density than a multi-family apartment complex on the same (or less) amount of land because of the number of dwelling units that can fit in the same space.

- Lot size can affect density. Larger lots with single-family houses take up more space, resulting in fewer dwelling units per acre than smaller lots with houses.

- When more than one dwelling unit is allowed in a building, a building’s height or mass can affect density. Larger buildings will result in higher density than smaller buildings when the dwelling units are the same size.

- When more than one dwelling unit is allowed on a lot, the size of the dwelling can affect density. Smaller dwelling units will result in higher density than larger dwelling units in a building of the same size.

- When more than one dwelling unit is allowed on a lot, the amount of the lot that a building covers can affect density. A multi-family apartment complex on a large lot with lots of area devoted to parking and recreational amenities in a more suburban setting will often be less dense than a garden apartment on a smaller lot in a walkable neighborhood near transit, amenities, and services in a more urban setting.

The Planning Department has studied how density looks in different areas of Albuquerque in several reports over the years.

- Urban Design Series (1997)

- Visualizing Density (2015)

The density that is appropriate is specific to each city. A sensible middle ground exists that allows for more density without developing buildings that are so big that they sacrifice the strong sense of community that makes our city thrive. If residential buildings are built increasingly taller, they become more expensive, since developers try to re-coup development costs, which can price out neighbors and lead to displacement. If residential homes are only provided as detached units, developers are unable to take advantage of cost savings from shared walls and infrastructure, which can also price out neighbors and lead to sprawl. Affordability is crucial to the story of density so that all neighbors are able to access the amenities that can come with increased density.

Even within a city, density will not look the same in every neighborhood. For example, multi-generational living is a traditional housing arrangement that should be honored by planning and zoning. Density that is appropriate for downtown should not be allowed everywhere in the city. The Integrated Development Ordinance sets out height limits and directs increased density to Centers and Corridors, where increased heights are more appropriate. It is also important to remember that increases in density can be achieved through seemingly smaller measures, such as by adding an extra floor to an apartment building, reducing lots sizes, building accessory dwelling units, or going from a single-family home to a duplex.

Many arguments debating the pros and cons of density take differing angles on the benefits of or drawbacks to density.

Benefits

The main benefit of increased density is that it often brings housing, jobs, transportation, and community amenities closer together. Clustering uses in one area makes it easier and more cost effective to provide infrastructure and services to support more residents and businesses. This holds true for streets, transit systems, deliveries of goods, health care, retail, schools, affordable housing – all systems that benefit from hubs of activity that draw people and from economies of scale (the cost per person, per area, or per mile goes down by serving more people).

This compact development pattern also provides environmental benefits compared to a low-density pattern of development with uses spread farther apart – often referred to as sprawl. Sprawl is often associated with many negative environmental impacts, including increased consumption of land and natural resources and lower air quality due to increased auto emissions from increased number and distance of vehicle trips.

Drawbacks

The main drawback of increased density is that it can lead to overstressing various systems when it becomes too difficult or problematic to serve too many people in a small area. Traffic is a good example. When uses are very far apart, people drive farther but faster, since fewer people are generally on the road at any one time. In a dense urban environment, people may not drive as far, but it may take longer, since speeds are often much slower due to the increased number of drivers on the road in a given area. That same urban environment will provide better opportunities to offer efficient and cost-effective transportation alternatives to driving, such as biking, walking, or transit.

Complexities

These basic arguments often overlook a more complicated reality on the ground. For example, some supporters of density may not acknowledge how different neighbors may experience density differently. For some lower-income people, more dense living, such as apartments, may not be a choice but rather an economic necessity. Higher-density neighborhoods that have fewer resources than surrounding neighborhoods may not experience the benefits density can bring, such as safe access to public transit or walkability to jobs, services, and amenities. On the other hand, in neighborhoods with more resources, opposition to density is often conflated with racist and classist misconceptions about who lives in apartments.